In Memoriam: Nikolai Orlov and the Fallen of Myasnoi Bor (Николай Орлов и павший Мясной Бор) (Published on 26/06/2024, latest update on 09/07/2024)

This blog also seeks to commemorate those who, much like Julius Erasmus, were committed to the recovery, identification and burial of fallen soldiers and endeavored to restore the names of the dead in the interests of their relatives. Gerda Dreiser from Bitburg, Toni Latschrauner from Meran and Lodewijk Johannes Timmermans in Ysselsteyn have already been reported on.

I. The “Forests of the Dead”

The Battle of the Hürtgen Forest in the autumn and winter of 1944/45 forms the background for Julius Erasmus’ work after the Second World War. The fierce and costly battles and the devastation of the previously vibrant forest led to contemporary reporting often linking the suffering of the fallen soldiers with the suffering of nature and referring to the Hürtgen Forest as the “Forest of the Dead”. Such “Forests of the Dead”, in which large numbers of soldiers perished during the Second World War, can also be found elsewhere. One particularly serious example is the swampy forest area of Myasnoi Bor northwest of the village of the same name in the Novgorod region in western Russia. In this difficult-to-access area, tens of thousands of fallen Soviet soldiers initially went unnoticed after the Second World War until Nikolai Orlov took it upon himself to recover them.

A story with striking parallels to that of Julius Erasmus and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest.

II. Myasnoi Bor and the Second World War

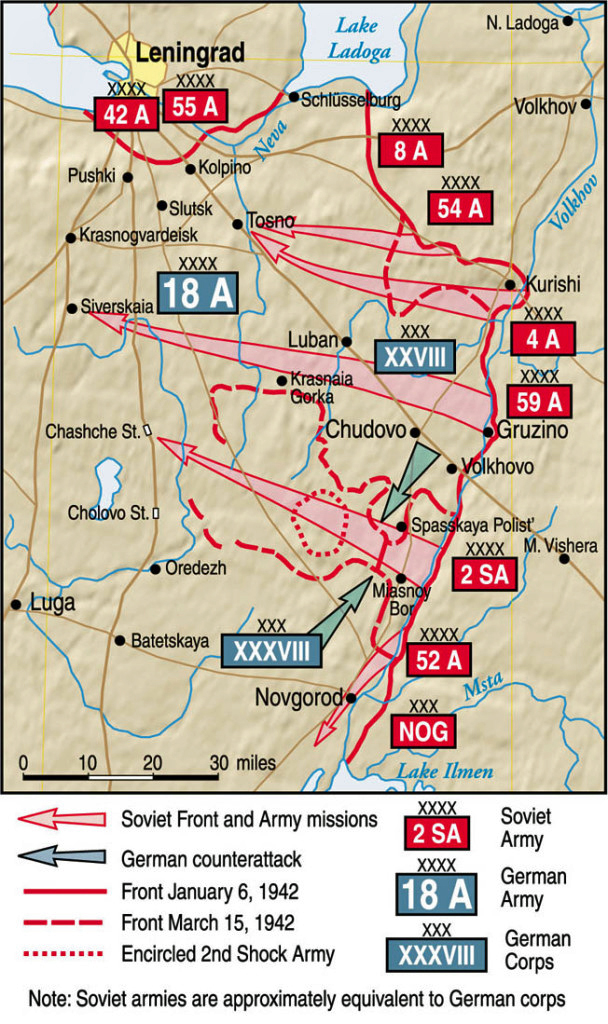

The village of Myasnoi Bor (Russian Мясной Бор, translated as “meat forest”) and the forest area of the same name in its northwest, the Smerti Valley, played an important role in the so-called Battle of Volkhov during the Second World War. The Battle of Volkhov, also known as the “Lyuban Operation”, was an offensive launched on 7 January 1942 by the Soviet troops of the so-called “Volkhov Front”, which was intended to break through the German blockade of Leningrad. As part of this operation, the Soviet 2nd Shock Army was encircled by German troops and completely destroyed by the end of June 1942.

The following description is based on the above cited descriptions from Wikipedia, detailed additional information on the Battle of Volkhov can be found in the article “Fighting on the Volkhov Front: The First Soviet Counteroffensive at Leningrad”.

1. The village and forest of Myasnoi Bor

The village of Myasnoi Bor, whose origins date back to the 15th century, is located in western Russia between Lake Ilmen and Lake Ladoga in the Novgorod district, approx. 30 km north of the city of the same name and approx. 100 km south of St. Petersburg. Immediately to the east flows the Pitba, a tributary of the up to 600 meter wide Volkhov river, whose extensive flood zones make the area and the surrounding forests swampy in many places. The road between Khudovo and Novgorod, which runs parallel to the Volkhov near the village, was a so-called “Rollbahn” (“taxiway”) during the Second World War and was a focal point of the Battle of the Volkhov. In the wooded area northwest of Myasnoi Bor, bloody and costly fighting between German and Soviet troops took place from the beginning of 1941 as part of this battle.

2. The Battle of Volkhov

After the blockade of Leningrad, the advance of the German troops was halted at the end of December 1941 in the Battle of Tikhvin. At this time, the front ran along the Mag-Kirishi railroad line and along the Volkhov River, where the troops of the 18th German Army faced those of the Soviet Volkhov Front (4th, 52nd and 59th Soviet Armies) and the left wing of the Leningrad Front (54th Soviet Army). The German blockade of Leningrad was to be eliminated by an offensive, for which the 2nd Soviet Shock Army was newly subordinated to the Volkhov Front.

On 14 January 1942, the troops of this 2nd Shock Army broke through the German defensive lines in several places, in which also Spanish troops of the 250th Infantry Division (the so-called “Blue Division”) participated, and established a bridgehead on the western bank of the Volkhov. The following day, they captured Myasnoi Bor and the forest area of the same name, and by 17 January, the German front had been completely breached. The width of the breach quickly widened to 25 km, but remained considerably narrower at Myasnoi Bor at 3 to 4 km. By the end of January 1942, the 2nd Shock Army had advanced almost 75 km and stood on the Novgorod – Leningrad railroad line at one of the entrances to the city of Lyuban. After the advance made no significant progress, the Soviet High Command concentrated its efforts on the conquest of the towns of Spaskaja Polistje and Lyuban in February 1942. To this end, three armies totaling more than 230,000 men were assembled to force a breakthrough on Lyuban. This was not successful, not least due to the supply of reserves taken from other front sections on the German side.

From 15 March 1942, the German side went on the counter-offensive, sealed off the Soviet breakthrough and encircled the 2nd Shock Army on 19 March 1942. On 27 March 1942, the 52nd and 59th Soviet armies were able to break the encirclement, but access to the positions of the 2nd Shock Army at Myasnoi Bor remained limited to a few kilometers. This is where the German troops once again cut off the 2nd Shock Army, which had been commanded by General Andrei Andreyevich Vlasov since 16 April 1941.

Despite the difficult situation, the commander-in-chief of the Soviet Volkhov Front, General Mikhail Semyonovich Khosin, insisted on continuing the offensive against Lyuban. It was not until 30 April 1942 that the attack was called off and the cut-off 2nd Shock Army was ordered to hold and defend its positions. Without food, medicine and ammunition, the Soviet soldiers had to hold out in the boggy terrain in water-filled positions. In a report on 11 May 1942, the commanding General Khosin proposed withdrawing the 2nd Shock Army across the Volkhov, giving up the terrain gains previously made. Permission was granted on 21 May and the retreat began on 24 May.

However, the German army recognized the intention of the Soviet retreat and finally closed the narrow retreat corridor near Myasnoi Bor on 30 May 1942. After bringing in additional reserves, the German troops began to smash the trapped Soviet troops on 22 June. The Soviet troops were almost completely routed in the final breakout attempts of the 2nd Shock Army on 24 and 25 June; up to 20,000 Soviet soldiers are said to have been killed in this breakout attempt alone.

On 12 July, General Vlasov, who had previously been in hiding, was captured by the Germans. He subsequently switched sides and later formed the so-called “Russian Liberation Army” (“Russkaya Osvoboditelnaya Armiya” (“ROA”)), also known as the “Vlasov Army”, which fought alongside Hitler’s Germany from late fall 1944 until shortly before the end of the war.

The Battle on the Volkhov failed and the Soviet troops suffered heavy losses. Estimates for all Soviet units involved range from around 95,000 dead and missing and more than 213,000 wounded to 149,000 dead and 253,000 wounded.

III. The Condemnation of the 2nd Shock Army

While the Germans had largely taken their fallen with them, the countless Soviet casualties of Myasnoi Bor, most of whom belonged to the 2nd Shock Army, were left to themselves for decades. This was mainly due to the swampy terrain, which was difficult to access, but also due to the involvement of General Vlasov, the commander of the unit at the time. After his defection in German captivity, he was taken prisoner by the Soviets shortly before the end of the war and was executed on 1 August 1946, among other things for treason.

His behavior was also blamed on the troops he commanded, in this case the 2nd Shock Army deployed at Myasnoi Bor. Although proven in the Battle of Volkhov, only commanded by General Vlasov from April 1942 onwards and with no connection to the Russian Liberation Army, which he only set up more than two years later, the 2nd Shock Army was nonetheless often regarded as a “traitor army” due to its connection to Vlasov, whose dead deserved no further attention.

Apparently rarely asked was the question of whether there might be a connection between Vlasov’s later behavior and the fact that in the Battle of Volkhov the Soviet High Command had initially ordered “his” already cut-off 2nd Shock Army to continue the offensive against Lyuban, then, after the offensive was called off, refused to allow it to retreat for weeks at Myasnoi Bor, despite completely inadequate supplies, thus promoting the subsequent tragedy.

IV. Nikolai Orlov and the Fallen of Myasnoi Bor

It was Nikolai Ivanovich Orlov, a native of Novgorod, who was the first to take care of the dead of Myasnoi Bor (for more information, see the Russian-language reports “The Valley of Memory” with many historic photographs by the “Dolina Search Expedition” and “Expedition into the Past – How the Search Movement was Born” by Lyudmila Ovchinnikova from 22/06/2015).

Born on 14/05/1927, his family was evacuated during the war and his father Ivan Ivanovich fought on the front against the Germans. After the end of the war and his father’s return home, life in the devastated Novgorod was not possible, so Ivan, who worked as a railroad worker, came to Myasnoi Bor with his family in 1946. Nikolai Orlov began to take an interest in the Smerti Valley, now known as the “Valley of Death” (Russian: Долина Смертти), and the remains of the fallen soldiers lying there amidst the destroyed vehicles and equipment.

Nikolai Orlov is quoted as follows (translation from the Russian language):

“Death Valley, as it was called, was two kilometers from the station and stretched 12 kilometers inland along the forest. Everything was burned, warped by craters. Even the grass did not grow.

(…)

It was bitter and sad that the warriors who fought in our places were not buried. As if they were not people. I was very worried, looking at this terrible picture. Everywhere were yellowed skulls. It seemed to me that there are thousands of them here.

(…)

I already knew that it was possible to determine who died here: if you find a black plastic capsule in a killed man’s pocket, there is a rolled up piece of paper in it, on which the last name, first name and patronymic are written, from which the fighter was called, his home address, information about his relatives. And I began to look for these capsules, carefully feeling the pockets.”

If he found such capsules, he wrote to the address given in them and informed of the whereabouts of the previously missing family member. He received grateful replies from surviving relatives who, in addition to finding out the fate of their loved one, were now also entitled to a state pension. The families of missing soldiers had no such entitlement. Nikolai Orlov recognized the value of his work and intensified it, spending almost all his free time searching for the dead soldiers. The first military cemetery was established near Myasnoi Bor.

Nikolai Orlov then stepped on a mine during his search and was seriously injured. This did not deter him from his work, and he resumed his search at the first opportunity. In the mid-1960s, the Orlov family moved to the village of Podberez’ye, around 10 km north of Novgorod, and in 1966 they moved on to a marshalling yard near Trubichino near Novgorod. Nikolai Orlov continued his work in the “Valley of Death” from his new place of residence.

At the beginning of 1968, he moved to Novgorod and started working for the chemical company “Azot”. After reporting on his work in the “Valley of Death”, first colleagues joined him as volunteers to support him in the search. By the following year, their number had grown to around 200. Thanks to press and television coverage and the efforts of the well-known writer Sergei Smirnov, Nikolai Orlov’s activities attracted nationwide attention, which further boosted further support for his search efforts.

Nikolai Orlov died on 13 December 1980 after many years of serious illness; he was only 53 years old.

V. The founding of the “Dolina Search Expedition” in Novgorod

His activities were continued by search teams from various parts of the country, e.g. by a group of students from Kazan University. In the summer of 1987, the search teams decided to concentrate their activities in an association based in Novgorod – the “Dolina Search Expedition” (Russian Поисковая экспедиция “Долина”), which was founded in February 1988. The first leader of the expedition was Nikolai’s brother, the Novgorod journalist Alexander Ivanovich Orlov.

In August 1988, “Dolina” carried out its first large-scale search, during which within ten days around 500 participants found the remains of 3,500 fallen soldiers on the battlefields of the 2nd Shock Army in the Novgorod region. In 1989, the search activities were extended to other districts of the Novgorod region, where there had previously only been smaller search teams, e.g. to Demyansk and Staraya Russa.

An article entitled “Der Vergessenheit entrissen” (“Torn from oblivion”) by Alexei Varfolomeyev, published in 1999 in the book “Erzählen ist Erinnern” (“Telling is remembering”) by Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge eV. (the German War Graves Commission), reports on a visit to Myasnoi Bor. It describes the search efforts of Nikolai Orlov and his brothers as follows (see “Erzählen ist Erinnern” (1999), p. 207 ff. [translation from German language]):

“We have arrived in Myasnoi Bor. This village is several centuries old. Alexander Orlov, my driver, says: ’30 kilometers from Novgorod.’ He is the youngest of five brothers and was born here in Myasnoi Bor – but only after the war. The eldest brother, Yevgeny, was killed at the front in 1943 at the age of just eighteen. Nikolai, the second eldest, was a railroad linesman. He went into the forest that rose darkly behind the tracks almost every day.

In the harsh post-war years, the forest fed people with berries and mushrooms. You could also find many useful things here, at the sites of the former battles – an axe, a saw, a spade or spare parts for all kinds of technical equipment. You could even pick up an American truck there if it could still be repaired. The rocket batteries – Katyushas – had been mounted on these American trucks during the war. When they broke out of the cauldron, the vehicles were rendered inoperable and left behind because there was no more ammunition for them anyway. These rusty vehicles are still standing in the forest today; some of them have now been overgrown by trees.

Nikolai Orlov often returned from the forest with a handful of identification tags. At home, he took strips of paper out of the plastic or metal capsules and wrote letters to the addresses given by the fallen soldiers to their relatives. Soon the other brothers went into the forest with Nikolai. And then disaster struck: Valery stepped on an anti-tank mine and was blown to pieces. This was followed by a second disaster: Yuri was killed by a splinter from an exploding shell. Only Nikolai and Alexander were left. They now went into the forest in pairs. The age difference between them was twenty years.

Alexander Orlow told me about their first ‘foray’: ‘There were white bones shimmering everywhere. There were tons of them. Among several hundred of our dead, we only found one German. ‘The Germans certainly didn’t discover him’, my brother said, ‘as they have usually taken all their dead with them’. I was later able to see this for myself. In the many years that we went into the forest, we only found a few dozen Germans in Myasnoi Bor.

The writer Sergei Smirnov was a kindred spirit of Nikolai Orlov. Together they tried to draw public attention to the Valley of Death near Myasnoi Bor with the unburied remains of soldiers of the 2nd Shock Army. In 1969, documentary filmmakers from Leningrad made the film ‘The Commander of the Valley of Death’ based on a book by Smirnov – the very name Smirnov gave to Nikolai Orlov. This film told the bitter truth about the fallen soldiers who had simply been left lying on the battlefield. But the movie was never shown.

Nikolai Orlov alone collected hundreds of identification tags and wrote letters to the relatives of the fallen. He became the initiator of a movement that set itself the task of burying the remains of thousands of these soldiers and identifying them. Nikolai Orlov is also no longer alive today. He had stepped on a mine twice in the forest and suffered serious injuries. He died of severe asthma in 1980.

There are three mass graves on the highway that I took with Alexander Orlov and his motorcycle to Myasnoi Bor. One of them was created during the war, even before the encirclement. The soldiers buried their fallen comrades here. In the second grave, the remains of 6000 fallen soldiers were buried, which had been collected by the members of a military unit in the 1950s. The third common grave was laid out by Nikolai Orlov.”

In 2008/2009, a memorial site was built near Myasnoi Bor, where more than 39,000 fallen Soviet soldiers, found between 1958 and 2022, were buried in mass graves.

VI. The “Dolina Search Expedition” today

Today, the “Dolina Search Expedition”, with 76 search teams and more than 1,000 members, is the largest association in Russia involved in the search for fallen soldiers. In addition to the organized search for the fallen of Myasnoi Bor and other places, it is also dedicated to preserving the memory of Nikolai Orlov.

According to its own information, the “Dolina Search Expedition” has found and buried more than 130,000 fallen soldiers in the area around Novgorod since 1988, and the names of more than 25,000 of them have been identified (see the expedition reports with many photos here, here and here).

The 1997 film “Angels of Death” by Dutch filmmaker Leo de Boer is about the search for the fallen at Myasnoi Bor, in which Alexander Orlov and his mother also have their say.

(Head picture: Soviet steel helmet in the Forest of Myasnoi Bor,

photographed by Evgeny Feldman, source: article “Explore the Valley of Death”)

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!