Mail Correspondence with Soldiers at War (“Feldpostbriefe”): Letter of German soldier Tobias Todtschinder from Russia to his daughter (Published on 17/07/2022)

Feldpostbriefe and their significance today

When researching Julius Erasmus, one inevitably comes into contact with letter correspondence between soldiers at war and their families from the time of the Second World War, such correspondence being called “Feldpostbriefe” in German. Be it messages about the death of a soldier, written by his superior to his relatives, which were later sent to Mr Erasmus as a hint for a grave search, or other correspondence between soldiers at war and their families at home. Since then, I have also been dealing more closely with field post letters from that time.

Feldpostbriefe are valuable contemporary documents that unfold their timeless message, especially in times like the present, and convey a vivid impression of what war means to all involved. They are a valuable tool to ward off the very beginnings of a renewed striving for war and perhaps to help prevent history from repeating itself once again and with yet more gruesome consequences for mankind. At present, war, weapons and the killing of people on a large scale are once again being drummed up forcefully, although for decades one could have had the vague hope that mankind had finally learned its lesson to some extent from the painful experiences of two world wars in particular. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case once again.

With this in mind, appropriate letters or letter excerpts from various sources will be published here from time to time in the section “Mail Correspondence with Soldiers at War (Feldpostbriefe)” as a reminder of what war means to man and mankind. To provide food for thought and in the unshakable hope that this may make a difference.

Letter of German soldier Tobias Todtschinder from Russia to his daughter

(source: v. Bebenburg, Ein Vermächtnis – Briefe und Gedichte gefallener Soldaten des Zweiten Weltkrieges [1955], p. 55 ff., translation from German language):

“To my dear Helga!

On guard I stood, in enemy territory. The night was starry. There I thought of you and of the battle in which we stand; there I thought about the value and the meaning of life. Many have already fallen, including some I knew. An hour ago he was alive, perhaps laughing, and then all at once his life ended. I saw it and experienced it, and with me all the others who are around me. Every moment can be our last, every action our last, and every word of ours can ring out in the ears of others as our last. Then, somewhere along the way, stands a makeshift wooden cross; the steel helmet covers its upper end: Born … Fallen … And what lay in between? What was erased? – What is no more? – What found an end? – Wasn’t the Heldentod [hero’s death], the commitment and the end of this life the best thing about it? And this commitment still, this end. – With many it was only ordered! The fewest have grasped the deepest meaning of their sacrifice – and with it also of their whole life. Grains of sand they were and still are. Washed up somewhere, carried along by the stream! – They do not know the goal and sense of these events. (Air raid warning!)

They let themselves drift, and only in insignificant things do they show their own will. When they are at the end, then somewhere a woman cries, children perhaps get into distress, parents mourn. But – there is only one grain more on the sand, no ship sinks, which carried precious property to a noble goal! – To be a ship and a helmsman at the same time, that is the meaning of life. You should want, not be wanted. All the striving of your life be for a holy task, a mighty goal. When you are at the end, then you have carried precious goods a bit forward and higher. – What is precious, the deepest reason of your being tells you, if you listen to it honestly, truly honestly. And even if you have to listen and search for a long time: That alone is worth a life! – I saw a whole people who were and are driven through life – and I saw those who believe that they can look down contemptuously on such people, but who themselves are only driven and wanted. – There the disgust seizes me – and you will understand me in this once. – Whether you dig your will into the stone of time with hammer and chisel, whether you reveal it in searching and finding, whether the waves of time break at you and find a new direction, or whether someone finds advice and help and support and trust in you, then, when he doubts – that is all the same. But a goal and a task you shall have at every hour of your life – and whenever you should be at the end, then lie between it and the beginning a way which you took – and – wanted to take.

Your father is still in the midst of the battle, but the victory that will be ours opens the way to a tremendous future. Countless tasks await us. –

Let us all show ourselves worthy of this coming time – including you.

Your father.”

Gefreiter Tobias Todtschinder, born on 11 September 1915 in Nuremberg, was killed on 28 November 1942 in Russia.

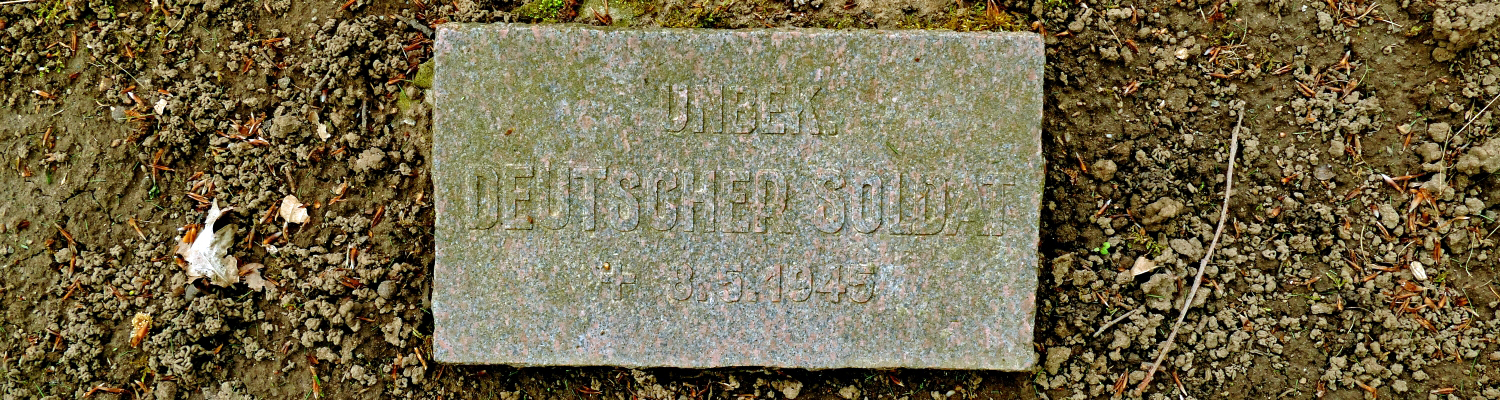

(Head picture: Military Cemetery Bensheim-Auerbach, April 2022)

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!