Mail Correspondence with Soldiers at War (“Feldpostbriefe”): The letters of German soldier Adelbert Rühle, 1939 to 1942 – part 2 of 4 (Published on 25/11/2023)

Feldpostbriefe and their significance today

When researching Julius Erasmus, one inevitably comes into contact with letter correspondence between soldiers at war and their families from the time of the Second World War, such correspondence being called “Feldpostbriefe” in German. Be it messages about the death of a soldier, written by his superior to his relatives, which were later sent to Mr Erasmus as a hint for a grave search, or other correspondence between soldiers at war and their families at home. Since then, I have also been dealing more closely with field post letters from that time.

Feldpostbriefe are valuable contemporary documents that unfold their timeless message, especially in times like the present, and convey a vivid impression of what war means to all involved. They are a valuable tool to ward off the very beginnings of a renewed striving for war and perhaps to help prevent history from repeating itself once again and with yet more gruesome consequences for mankind. At present, war, weapons and the killing of people on a large scale are once again being drummed up forcefully, although for decades one could have had the vague hope that mankind had finally learned its lesson to some extent from the painful experiences of two world wars in particular. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case once again.

With this in mind, appropriate letters or letter excerpts from various sources will be published here from time to time in the section “Mail Correspondence with Soldiers at War (Feldpostbriefe)” as a reminder of what war means to man and mankind. To provide food for thought and in the unshakable hope that this may make a difference.

The effects of political indoctrination on children and young people

Among the most harrowing evidence of what political propaganda is capable of are letters written by young German soldiers during World War II, such as those already published on this blog (see, for example, the letter by Franz Krügner). Exposed from childhood to “education” in the sense of the prevailing ideology, they had internalized the latter so deeply that they could often hardly wait to become soldiers and to be allowed to make their contribution to the realization of the goals that were conveyed to them as having no alternative.

The Feldpostbriefe of Adelbert Rühle

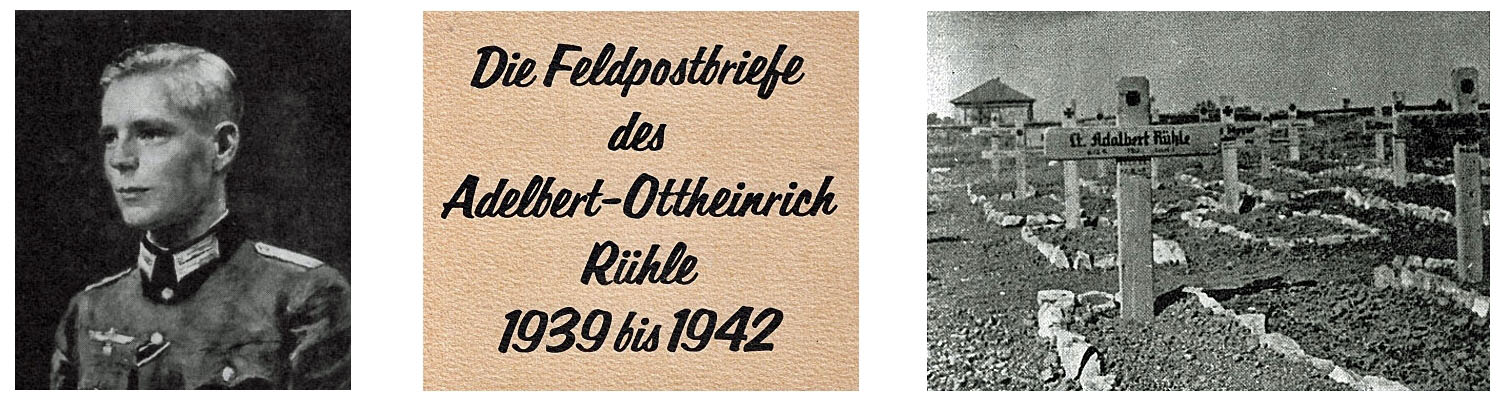

Adelbert Rühle, born on 23/09/1923 in Posen, was one of these soldiers. Not even 16 years old, he volunteered for military service in the fall of 1939. He fell on 07/08/1942 as a lieutenant of 6th co./InfRegt 120 (mot.) near Kalach/Russia and was buried at the military cemetery Krassnye Skodowad near Kalach. Beginning as a recruit during his basic training in October 1939 until his death on the Eastern Front in August 1942, he wrote numerous field letters to his family, in which he described his spiritual life and his soldierly motivation with a frankness that is sometimes difficult to bear from today’s perspective.

His letters were published during the war in the booklet “Die Feldpostbriefe des Adelbert-Ottheinreich Rühle 1939 bis 1942” in order to show, according to the propaganda of the time, “the mental development of a German boy into a soldier, into an officer” (according to the preface op. cit., p. 5). A new publication took place in 1979, now containing an admonition for reflection and peace (preface op. cit., p. 6).

Adelbert Rühle’s letters are a timeless warning to be vigilant against totalitarian political systems and their characteristic mechanisms.

They exemplify the consequences of a regime that already took possession of children and young people and educated them through propagandistic indoctrination to become compliant instruments of the ruling ideology, who were as gullible as they were unconditionally committed, in word and deed, to the slogans conveyed to them. The dramatic consequences are well known.

Some of these letters will be reproduced here, spread over several parts. Further published are: Part 1, Part 3 and Part 4.

Undated letter from Adelbert Rühle to his father (source: Brunhild Rühle, “Die Feldpostbriefe des Adelbert-Ottheinreich Rühle 1939 – 1942” (1979) [hereafter abbreviated to “Feldpostbriefe Rühle”], p. 24 f. [translation from German language]):

“Dear Dad,

You went through a difficult time in the last war and were therefore prepared for anything when you heard that I was at the front. I only got a glimmer of what you experienced and achieved, and that’s why I’m in awe that you suffered so much that I volunteered so young when you lost both your brothers in the war. But you understand me, you also volunteered for the Great War, just like our grandfathers and great-grandfathers did in 1813.

And you are right to write to me that, however small the mission, you are still indispensable if you carry it out completely without standing out. Being a soldier doesn’t mean doing glorious deeds, and that’s especially true for us infantrymen. And if you do as much as you can in your position, however small, then you stand for the whole of Germany, for the heritage of our fathers and for the future of Germany’s children, however insignificant the deed may seem.

Even if you have had to go through a lot of hardship, we are now using all our strength as the same soldiers as you, for the same goal. Your Addi.”

Letter from Adelbert Rühle to his mother dated 05/03/1941 (source: “Feldpostbriefe Rühle”, p. 31 ff. [translation from German language]):

“Dear Mother,

Did you hear the news on the radio on Sunday morning about the German troops invading Bulgaria? Then it’s probably going to start down there this spring, it’s not far from there to Greece.

The weather is already warm here. The sun has the same power it has at home during summertime. We have now driven through beautiful countryside in the sunshine again. Of course, there won’t be any mail any time soon. But I hope it won’t be long now and that you will receive my letters soon.

We see beautiful, magnificent mountains and rivers, and yet we always feel that we could not always feel at home here. There is no other country in the world with so much culture, cleanliness, work ethic and warmth of spirit. We are all somehow moved by the will to give our lives some kind of meaning, to achieve something, to fight for it if necessary.

There can be nothing better for us than to stand up for this Germany, to accept hardship, because we know that it is not in vain and that Germany will live forever. Our life and the life of the nations cannot be a coincidence, it is God’s will, that is my faith in God. Our fate and that of the nations at large is not decided by chance, by material and quantity, but by the commitment and the will to live, the right to live, that is his justice for me.

That is why I believe so firmly in Germany’s survival, in its eternity. This is no question of reason, you have to believe in it, otherwise the world would be too empty and sober for us, in which we only live finitely.

Yesterday the colonel was here and said I would probably be transferred soon. That wouldn’t be good, I would feel completely lonely without my good comrades with whom I had settled in so well, 3000 km away from home … the company is a soldier’s second home. But I would soon settle back in there too, if I had to. On deployment, I would be »rifleman one« anyway. But I don’t have a choice, I have to wait and see.

And the fact that you all trust in us back home makes the small inconveniences seem little and gives us courage time and again. And if we don’t get to see a bed and have to eat canned food until Christmas, »the day will come!«. I’m already dreaming about it and imagining how I can contribute then.

But I just wanted to send you a quick greeting.

Please say hello to the little ones from their Addi brother. I don’t want them to forget him once he comes home as a mossy warrior. Your Addi.”

Letter from Adelbert Rühle to his mother dated 18/03/1941 (source: “Feldpostbriefe Rühle”, p. 34 f. [translation from German language]):

“Dear Mother,

On Heroes’ Memorial Day, which was celebrated very nicely by the regiment with a field service and a march past, I was promoted to sergeant by the colonel and transferred to the sixth company, the rifle company. He said that it was probably difficult to be a superior at such a young age, but if you could deal with people properly and, above all, always be a role model yourself, then significantly older men could also recognize you as a superior and even become attached to you. I would probably be going to weapons school soon and should now prepare for it in the rifle company. Hopefully I wouldn’t get away during the deployment, then I would be heartbroken! Messing about in theory while my comrades are fighting to decide Germany’s future and then coming back afterwards as their superior – I definitely don’t want that. To be able to lead a group on a mission, I’d have to work really hard, but if we have another 14 days, I’ll manage, maybe we’ll even stay here for months.

Of course I would have liked to stay in our company. I think I could have »asserted myself« here too. All my comrades and superiors are sorry, but I get on well with everyone, I don’t have any enemies in the company.

Now I’d like to send home my old, well-deserved private’s rank insignia (“Gefreiten-Winkel”), which I received »for bravery in the face of the enemy« and proudly wore for three quarters of a year. A reminder of the beautiful, carefree time – serving with many good comrades as an »old« soldier, that was a wonderful time. I didn’t get upset about anything anymore, I knew all the tours, and when it was the end of duty, it was just the end of the day, then I thought … »Götz« [short for Götz von Berlichingen, hinting at a certain insult famous in Germany]… Who knows if I’ll ever be that carefree again in my life. But if you don’t have any worries, you always create some.

Best wishes to you all. Your Addi.”

Letter from Adelbert Rühle to his family dated 07/08/1941 (source: “Feldpostbriefe Rühle”, p. 43 ff. [translation from German language]):

“My dear Ones,

The night before last we combed through two villages and took 384 prisoners, yesterday we made a reconnaissance patrol (motorized), suffered a little from air raids and then drove through the night from yesterday to today.

Today we had some wonderful peace and quiet again. The mail came again, two letters from Mum and cigarettes and today we even had chocolate. So our life is quite idyllic.

Maybe it’ll continue tonight, so you have to be able to make every minute as beautiful as possible, and I’m quite good at that. It always depends on yourself whether you feel happy and can give yourself pleasure, even with the smallest of means, just with »blue skies and green spring soil«.

Why shouldn’t we be happy! To be able, at such a young age, to stand up with our lives for our people and our fatherland, is the highest good. To be able to protect our great past, our high, inner values, our wives and children and thus to be able to pave the way for our future, which lies ahead of us with so many great tasks, is a surely great happiness. All the smaller and larger deprivations are so small in comparison, these small comforts alone cannot make us happy. Of course we, Reini and I, like many others of the same age and like you too in the last war, »had nothing of our youth«, as they say, and our youth is really hard because we were torn away from our parents’ home so early and so abruptly and were unable to experience many joys. But instead we have a wonderful, great and beautiful future ahead of us with so many great tasks, and that is a much greater happiness. And it is precisely these hardships, which we often have to endure, that also help to educate us. Even though so much seemed pointless during those two years and a lot of precious time passed without me being able to learn anything or make any progress, this time also contributed to my education. It was precisely this time that made me humble. This is so important in today’s Volksgemeinschaft that it will benefit my whole life.

And although I didn’t make much progress on the outside during the war, I won on the inside. And I know for myself that I was never a coward and that I was always in control of myself and did my duty, even in the heaviest fire. That is proving yourself at the frontline for personal purposes, and that is much more important than any external badges. All these little things can no longer make me small, just like this cursed rain, which is why I have to stop now. Altior adversis! [Exalted above adversity!]

Best wishes to you all. Your Addi.“

To be continued. Further published parts of the series: Part 1, Part 3 and Part 4.

(Head picture: Adelbert Rühle and his grave,

from: “Die Feldpostbriefe des Adelbert-Ottheinreich Rühle 1939 – 1942”, p. 60, 90)

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!