Mail Correspondence with Soldiers at War (“Feldpostbriefe”): The letters of German soldier Adelbert Rühle, 1939 to 1942 – part 4 of 4 (Published on 14/06/2024)

Feldpostbriefe and their significance today

When researching Julius Erasmus, one inevitably comes into contact with letter correspondence between soldiers at war and their families from the time of the Second World War, such correspondence being called “Feldpostbriefe” in German. Be it messages about the death of a soldier, written by his superior to his relatives, which were later sent to Mr Erasmus as a hint for a grave search, or other correspondence between soldiers at war and their families at home. Since then, I have also been dealing more closely with field post letters from that time.

Feldpostbriefe are valuable contemporary documents that unfold their timeless message, especially in times like the present, and convey a vivid impression of what war means to all involved. They are a valuable tool to ward off the very beginnings of a renewed striving for war and perhaps to help prevent history from repeating itself once again and with yet more gruesome consequences for mankind. At present, war, weapons and the killing of people on a large scale are once again being drummed up forcefully, although for decades one could have had the vague hope that mankind had finally learned its lesson to some extent from the painful experiences of two world wars in particular. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case once again.

With this in mind, appropriate letters or letter excerpts from various sources will be published here from time to time in the section “Mail Correspondence with Soldiers at War (Feldpostbriefe)” as a reminder of what war means to man and mankind. To provide food for thought and in the unshakable hope that this may make a difference.

The effects of political indoctrination on children and young people

Among the most harrowing evidence of what political propaganda is capable of are letters written by young German soldiers during World War II, such as those already published on this blog (see, for example, the letter by Franz Krügner). Exposed from childhood to “education” in the sense of the prevailing ideology, they had internalized the latter so deeply that they could often hardly wait to become soldiers and to be allowed to make their contribution to the realization of the goals that were conveyed to them as having no alternative.

The Feldpostbriefe of Adelbert Rühle

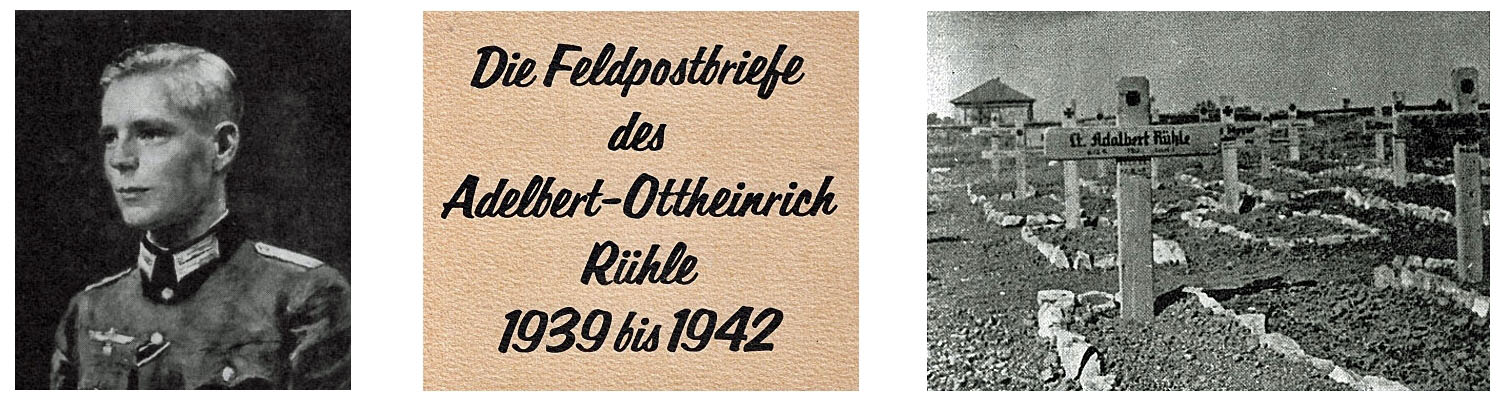

Adelbert Rühle, born on 23/09/1923 in Posen, was one of these soldiers. Not even 16 years old, he volunteered for military service in the fall of 1939. He fell on 07/08/1942 as a lieutenant of 6th co./InfRegt 120 (mot.) near Kalach/Russia and was buried at the military cemetery Krassnye Skodowad near Kalach. Beginning as a recruit during his basic training in October 1939 until his death on the Eastern Front in August 1942, he wrote numerous field letters to his family, in which he described his spiritual life and his soldierly motivation with a frankness that is sometimes difficult to bear from today’s perspective.

His letters were published during the war in the booklet “Die Feldpostbriefe des Adelbert-Ottheinreich Rühle 1939 bis 1942” in order to show, according to the propaganda of the time, “the mental development of a German boy into a soldier, into an officer” (according to the preface op. cit., p. 5). A new publication took place in 1979, now containing an admonition for reflection and peace (preface op. cit., p. 6).

Adelbert Rühle’s letters are a timeless warning to be vigilant against totalitarian political systems and their characteristic mechanisms.

They exemplify the consequences of a regime that already took possession of children and young people and educated them through propagandistic indoctrination to become compliant instruments of the ruling ideology, who were as gullible as they were unconditionally committed, in word and deed, to the slogans conveyed to them. The dramatic consequences are well known.

Some of these letters will be reproduced here, spread over several parts. Further published are: Part 1 and Part 2 and Part 3.

Letter from Adelbert Rühle to his mother (source: Brunhild Rühle, “Die Feldpostbriefe des Adelbert-Ottheinreich Rühle 1939 – 1942” (1979) [hereafter abbreviated to “Feldpostbriefe Rühle”], p. 91 ff. [translation from German language]):

“Russia, 28/7/1942

Dear Mother,

we’ve been lying in the same position for two days now, which is a rarity. That’s why I’m feeling really Sunday-like today: just washed yesterday (water nearby, but in the direction of the Russians), slept in until 4 o’clock this morning, that’s like Sunday! The day of the week doesn’t matter, you have to celebrate the festivals as they fall, our old principle.

The Russian doesn’t appear to be completely satisfied yet. Both sides are quite active in the air, but we are on the ground and take the air more as a spectacle. How many beautiful newsreel shots I could have taken now, but of course the films are safely stored on the vehicle again.

Our anti-tank defense is fabulous. Our kill rates must be tremendous again. They can no longer harm us if we have our holes. But above all because we all have a very cold calm in the face of them. We watch calmly from our holes to see if they are pointing their barrels at us, and we know that they are much more afraid than we are and that, at worst, they could just as easily roll through.

The feeling of our superiority is so great for all of us, especially in the attack. Although we actually have a lot more peace and quiet now, we all want to get back in front, just get back to it, waiting and being powerless against heavy weapons is what we like least.

This spirit passes from the best to all, and the newcomers are also drawn to it, even if it sometimes causes a little friction. And I know exactly who my best people are. You have to do the same today, it always comes down to lone warriors, who are worth much more than 50 mediocre, lukewarm ones, not to mention cowards. And the best are mostly old soldiers, although there are always fabulous guys among the replacements.

Some people are worried that after the war, the best jobs will be given to those who are now staying back home. We can have confidence that no injustice is being done here, although there is always a danger. After all, everyone knows that we can never be rewarded with the ‘thanks of the fatherland’. We didn’t go to war so that we would be favored later. We would never have taken so much for that.

There will always be injustice, just as there will always be two kinds, and many of today’s home warriors are certainly the sons of those who stayed back at that time. It’s best not to complain about that at all!

We will always have one thing over them that no one can take away from us: our pride, our honor!

How stupid to harbor post-war thoughts now, when we all know that the end is far from in sight and we are not deluded!

The childlike imagination, which has remained childlike still, likes to wander into this fairytale land.

Mail is very scarce now. Another letter arrived yesterday.

I’m really looking forward to your parcel. I’m already thinking of new wishes: Busch! If possible, a small volume of poetry like »Kritik des Herzens« [‘Critique of the Heart’]. There are still so many poems by him, and they give ‘us’ here so much joy. I was also thinking of Eugen Roth or Reuter. As for newspapers, I would still like to have the ‘Lustige Blätter’ from time to time. It’s probably the best funny paper with nice caricatures. I’ve already written the other things by airmail. But my ever-growing wishes are now completely fulfilled! Addi.”

Last letter before Adelbert Rühle’s death, found with him on 7/8/1942 (source: “Feldpostbriefe Rühle”, p. 94 ff. [translation from German language]):

“Dear Parents,

my thoughts are now finding it difficult to follow your back and forth, especially as they always have to think ahead to allow time for the field post. But I’ve been thinking about the 23rd [the day of his sister Reinhild’s wedding to his friend Jochen] for a long time, you can believe it, and I’ve almost been waiting for the day when it’s time to congratulate you on your wedding. Congratulations sounds so formal, you know how much I wish you happiness.

I know that your thoughts will go to me on that day and I hope that you will then have my letter in your hands, and then it will be exactly as if we were experiencing it together and talking to each other.

I can see you sitting in our dining room by the candlelight of the Blaker in the old furniture, which has already become a piece of home to us because we celebrated many a party in it, and I feel completely among you. My thoughts go back to our engagement, Christmas, when we sat around the round table, all together, even in the middle of the war, and it was probably the most beautiful celebration we ever had. I think that’s how you will sit around the round table now, surrounded by people who are close to us. You have already written to me about who will be among you, and I know almost everyone. I hope you won’t miss the solemn ‘grains of gold’ of my toast too much, and I only have one request: that you don’t let the fact that I’m not among you spoil the festive mood one bit. You know, dear parents, that I have always asked you not to postpone the wedding because I’m not here: That would be a sad feeling, a hindrance and an obstacle. I really mean it, I was never in favor of the long wait!

And if I know that you are celebrating this festival in unhindered joy, then it won’t be difficult for me not to be there. It’s so self-evident that we don’t need to say a word about it.

Surely you have enough justification to celebrate carefree even during the war, because you have all made sacrifices and hardships in this war and continue to do so as only a few do, just as you did in the previous war, because they are always the same. And that is why you should not think of us wistfully in a happy hour! You know that it’s the best feeling for us to know that we have peace and quiet at home, joy and, especially with the little ones, carefreeness. You, dear mother, know that I would much rather receive news of your happy times, even if they are rare, than if you were to write letters of complaint, as so many unfortunately do.

It’s a nice feeling to know that everything will still go its way. A wedding in particular, the day on which you want to start a new family, should be celebrated with carefree cheerfulness, even during the war, as a celebration whose purpose is for the future. The joyful hopes associated with it, because it opens up a whole new life, should not be smothered in gloom. The spirit in which two people begin their journey together should be joyful and confident, even now in times of war. Its deep meaning, the path to the child, becomes particularly valuable and great, I would like to say sacred, at this time when so many comrades have to bite the dust. At a wedding during the war, it should become very clear that they have not fallen in vain. You feel it much more strongly here than at a big rally with roaring words.

We will probably always live with the feeling that we have to help complete her life, which was taken so early. This feeling comes naturally to us, especially in days like these. I think of the words of Flex: ‘The mother who cares for a little child cherishes a little flower over my grave’.

We all see the highest meaning of this feast in the child, and how beautiful it is that the ‘little ones’ walk carefully behind Reini [his sister Reinhild] with the veil with big, solemnly shining eyes. I can really see it in front of me. Their eyes with a festive gleam, because they always have a strong sense of celebration. (However, if Borstel is out of character and beams with cheekiness instead of solemnity, then I have prophesied wrongly again).

I would love to know what idea of the day lives in those little hearts. It must be beautifully clear and pure. After all, children are part of this celebration. We can’t think of a celebration without them.

Through them, this day also loses any oppressive sadness of parting. It ensures that we never become strangers to each other, no matter how long and far life separates us.

And I also know very well, dear parents, that we siblings will always be close to each other, just as we can never be estranged from you! In this too, the war was probably a school for us, in which we learned to accept long separation without sorrow, and yet never to become estranged, on the contrary, to grow ever closer inwardly. After all, life demands separation from us and we don’t want to stand in its way. We know that it will never drive us apart.

Now that all gloom has been nipped in the bud, I want to be with you with a happy heart, with our happiness! Nastrowje!“

With the letter, the following poem was found (source: “Feldpostbriefe Rühle”, p. 99 ff. [translation from German language without implementing the rhyme scheme]):

“COMRADE DEATH

Death, comrade, you beside me,

Who always rode with me,

You walk with me; I walk with you

In the field every step.

How long we’ve been together

As constant companions!

Had I never seen you so close,

I would not yet be a rider.

I didn’t know you as a child,

I laughed at you.

Now I’ve recognized you for a long time,

In many a difficult night.

When you with bare, hard steel

You struck out wildly,

Many a time you‘ve already filled me

With fear and horror.

Since you played with flesh and blood

Blind as the scythe goes,

Rummaged in human bodies

And mowed away life.

And then when I was so still and stiff

I saw my comrade,

I knew then that it was not him,

He was no longer there.

But his gaze that saw you

In his last breath,

Was peaceful, and beautiful

The expression that he wore.

And peace entered my heart now –

You were so close to me,

That I saw you without fear and pain

I saw you standing close to me.

And as if in a dream I spoke to you

And only asked ‘when’ …

And quietly you spoke to me now:

‘Everyone will get their turn.’

Where in this world, comrade,

to riders still exist without you?

If you did not join us,

There would be no valiant fighters.

For he who does not know fear and terror,

He cannot be brave.

Who really burns for the flag,

He puts everything into it.

Now I won’t ask you ‘why’ anymore

And don’t ask you ‘when’ either.

Because you are silent and you are mute

Like every real man.

So, comrade Death, you beside me,

Who always rode with me,

You go with me, I go with you

Until the last step.”

Jochen Fritsche was Adelbert Rühle’s older friend by six years. Jochen married Adelbert’s sister Reinhild on 23/8/1942; he was killed near Königsberg on 24/2/1945.

The news of Adelbert Rühle’s death reached his family the day before his sister’s wedding and had to be kept from his mother for that day.

The End. Further published parts of the series: Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

(Head picture: Adelbert Rühle and his grave,

from: “Die Feldpostbriefe des Adelbert-Ottheinreich Rühle 1939 – 1942”, p. 60, 90)

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!