Thoughts on war: Gustave M. Gilbert and the “Nuremberg Diary“ – Mechanisms of motivating people to participate in war and for the elimination of resistance (Published on 17/05/2024)

If you ask yourself how certain political developments, especially dictatorships and wars, could come about, it is well worth taking a look at the book “Nuremberg Diary” by the American psychologist Dr Gustave M. Gilbert.

I. Gustave M. Gilbert and his “Nuremberg Diary”

Gustave M. Gilbert was born on 30/09/1911 in New York City and died on 06/02/1977 in Manhasste/NY. As the son of German-speaking parents, he was an employee of the US Army’s intelligence service during the Second World War and was used for prisoner interrogations. After the war, his knowledge of the German language led to his appointment to the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, where he examined the defendants in the Nuremberg trials against representatives of Nazi Germany and conducted extensive individual interviews with them. He documented these interviews in a detailed diary, in which he also provided detailed factual and atmospheric information on the defendants’ reactions to the trial. He later reported on these conversations in the aforementioned “Nuremberg Diary”, which was first published in 1962.

II. Gilbert, Göring and how to motivate people for war

Particularly noteworthy is a conversation documented in this diary that Gustave Gilbert had with the former second man in the Nazi state, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, on the question of what measures could be used to persuade the people to support a war and how resistance could be eliminated.

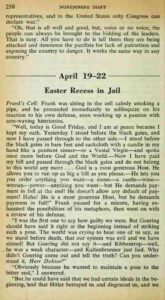

The respective pages 255 and 256 from the “Nuremberg Diary” (1962) can be viewed here:

Gilbert reports (ibid., p. 255):

“We got around to the subject of war again and I said that, contrary’ to his attitude, I did not think that the common people are very thankful for leaders who bring them war and destruction.”

Göring answered (ibid.):

“Why, of course, the people don’t want war. Why would some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best that he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece. Naturally, the common people don’t want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship.”

Gilbert objected (ibid., p. 255/256):

“There is one difference. In a democracy the people have some say in the matter through their elected representatives, and in the United States only Congress can declare war.”

And Göring’s reply (ibid.):

“Oh, that is all well and good, but voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.”

III. Food for thought

The question of why “would some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best that he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece” is as valid as it is topical today. Just as unchanged are the methods used to persuade people to participate in political agendas in which they often have nothing to gain but a great deal to lose.

If you pay attention, you can observe how often political protagonists use the tried and tested method of accusing those with views that deviate from the government line of endangering others, right up to the present day, and often with success.

Indeed, why would anyone “want to risk his life in a war when the best that he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece”? And why should a policy that purports to serve the good of mankind not only demand this of him in the first place and in the knowledge that “naturally, the common people don’t want war”, but even use perfidious psychological tactics to make him join in – against his own interests – and silence dissenting voices?

Let us pay attention and stop allowing ourselves to be divided. Let us say no.

(Head picture: US Military Cemetery Henri-Chapelle/Belgium,

October 2018)

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!