Pillbox Battles: US attack on pillbox 227 on the Harresberg near Lammersdorf in September 1944 (Published on 22/12/2022)

The battles for some of the Siegfried Line pillboxes in the Hürtgen Forest area shall be described here in more detail in a series, because it was often Julius Erasmus who later recovered, identified and buried the victims of these battles. For a better understanding, the article “The battle for Siegfried Line pillboxes in the Hürtgen Forest area” should be read first, which describes the initial situation of the battles and some of their characteristics in more detail.

I. Location and construction of pillbox 227

Only a few reports are known here so far that describe in detail battles around Siegfried Line pillboxes in the Hürtgen Forest area, which occurred in large numbers between September 1944 and February 1945. One of them comes from the US Army and relates to an attack in September 1944 by the 39th Regiment of the 9th US Infantry Division on a German command post, which at the time was located in a pillbox on a hilltop, the so-called Harresberg, above the present-day highway B266 between Lammersdorf and Rollesbroich. The attack is described in more detail in a document entitled “Report on Breaching of the Siegfried Line” of the Engineer Section, XVIII Corps (Airborne), dated 28 January 1945 (afterwards “US Report” or “Report”).

The pillbox in question was a battalion or regimental command post of the Regelbau 117b type, listed in the Wehrmacht map of the time as pillbox 227. A schematic representation of this pillbox can be found further down in the picture gallery. The Regelbau 117a shown there is identical to the type 117b concerned here, the latter, however, lacks the so-called flanking system (“Flankierungsanlage”) that protected the entrance area. The structure was usually built into the ground as to be level with the terrain around it. From the B266, the location of the pillbox – then as well as now – cannot be made out, nor is the road easily visible from the site of the former pillbox.

II. The attack

The Report shows, on the one hand, the brute methods used by the US Army against the the Siegfried Line pillboxes in order to eliminate them at all costs, and on the other hand, the martyrdom that some bunker crews inside took upon themselves in order to avoid surrender at all costs – possibly for the reasons described in more detail in section V. of the introductory article. it starts with setting out some tactical considerations that US troops followed when attacking pillboxes (Report, p. 6):

“TACTICS USED IN ASSAULTING PILLBOXES.

Frontal attacks on pillboxes are avoided in an effort to evade the concentrated fires from the embrasures. The blind approaches to a pillbox can be quickly determined by thorough reconnaissance previous to the attack. In many instances, the occupants of a pillbox have surrendered readily upon finding that our forces have worked their way to the rear of the occupied pillbox. When stubborn resistance is met, available tanks, tank dozers, AT guns, bazookas and 155 [mm] self-propelled cannons are brought up to fire on the embrasures. The fire from these weapons usually induces the occupants to surrender. In some few instances, the doors to the pillboxes have been sealed and the pillbox covered with earth by the use of a tank dozer.”

Subsequently, the course of the attack on pillbox 227 is described in more detail (Report, p. 6/7):

“Company ‘K’ of the 39th Infantry reduced a pillbox on the main road from Lammersdorf to Rollesbroich on 22 December [Note: correct should be September] [1944]. It was mostly recessed in a hollow in the ground, with steep banks, accessible by steps leading to the entrance. The ceiling was approximately six feet thick covered with five feet of earth. There were two doors in the front of the box with apertures through which machine guns were fired.

Upon the arrival of the company at the pillbox, some members of the assault team were able to get on top and around the blind sides of the box; from these positions bazookas were fired and pole charges were placed against the outer entrance door. These two methods failed to dislodge the occupants. Gasoline was poured under the door and ignited with a thermite grenade; this method was unsuccessful. The next morning further attempts to cause surrender were met by bursts of machine gun fire by the occupants. A tellermine and one beehive charge [Note: A special explosive charge in the shape of a beehive, used primarily to blow holes in floors and walls of structures] was placed on the ventilator top of the pillbox blowing off the pipe. Twelve tellermines were then placed in the opening where the ventilator had been, followed by another charge of 24 tellermines. This failed to penetrate the box. A charge was then placed to blow away the earth in order to get to the concrete on the top side of the box. From 6 to 8 beehive charges were used in succession each calculated to blow through approximately 2 ½ feet of concrete. Finally, 3 beehives in the hollow created by the previous beehives were used. The total penetration of these charges amounted to 2 ½ feet. Between these attempts, bazookas and flame throwers were used against the apertures with no avail.

Finally, a charge of approximately 300 pounds of TNT was placed in the hole on top of the pillbox, tamped and detonated. After the explosion, the occupants came out and surrendered. The occupants reported that some smoke entered through the firing apertures, but none through the vents or doors. Flame throwers had no effect and no gas entered under the door, but the occupants sensed the odor of burning phosphorous. The candle light dimmed and went out several times. The occupants left the pillbox not because they believed one of the entrances was already blocked and the other sufficiently blocked to make their fire ineffective, and it would enable charges to be eventually placed against the door. There were 30 men in this pillbox.”

This attack is apparently also described in the division history of the 9th US Infantry Division, although the description is not only more lurid, but also deviates in details from the aforementioned descriptions. It states (cf. Mittelman, Eight Stars to Victory – A History of the Veteran Ninth US Infantry Division [1948], p. 252):

“What happened to one pillbox facing Company K of the 39th Infantry illustrates both the kind of battle waged by the Nazi soldiers and the coordination rendered by its 15th Engineers [15th Engineer Combat Battalion]. It was on September 23rd that a particularly vicious group of Germans was encountered by Company K in the Lammersdorf sector … defending a concrete structure. This pillbox was built so well that it required artillery, anti-tank rockets, smoke, 24 pounds of dynamite, detonation of 18 Teller mines and 400 pounds of TNT to force its 38 occupants to surrender … and the only after 12 hours of incessant pounding! When the emplacement’s defenders surrendered finally, they had broken eardrums and were suffering from severe shock.”

III. For explanation

There is a German translation of the Report (cf. German Federal Archives document RH 11/III/101; also printed in Groß, Westwallkämpfe [2015], p. 43), which, however, lacks information on the pillbox location, sometimes causing confusion as to where the described attack occurred, due to the large number of pillboxes formerly located in this area (for instance, Siebertz, Höhe 554 [2010], p. 98, attributes it to pillbox 217, located further west and on the other side of the B266; his description of the fighting around pillbox 227, which partly differs from the US report, can be found on p. 105). However, the description in the Report of the location and construction of the two-entrance pillbox in question and its occupancy by at least 30 people point to pillbox 227.

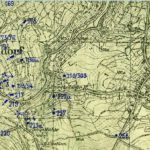

Contrary to the Report’s assumption, the entrances and doors of the Regelbau 117b in question were located not on the front, but on the rear side of the pillbox, facing away from the enemy. In the case of pillbox 227, they were probably located in the embankment on its eastern side. The fact that, according to the Report, the attacking US soldiers were fired at from the entrances indicates that they approached the pillbox from its rear, possibly via a dirt road that branched off from the main road, passing at close distance east of it (cf. the excerpt from the Wehrmacht map in the picture gallery).

Today, this dirt road no longer exists, and there is not much left of pillbox 227 either. Whether the latter was blown up is unclear. At least it was backfilled and grounded over, its former location stands out from the surrounding pasture land only as a flat hill. However, the separate fencing-off of a roughly square area at the end of a dirt road and the vegetation there, which differs in color from its surrounding area, make it rather easy to identify.

Although, according to the documents currently available, none of the soldiers buried in the military cemetery in Vossenack has a recognizable connection to pillbox 227, the Report is nevertheless an impressive testimony to the intensity of the fighting at that time around the Siegfried Line pillboxes in the Hürtgen Forest and to the circumstances under which soldiers on both sides lost their lives there.

(Head picture: Location of pillbox 227

on the Harresberg near Lammersdorf, August 2022)

Many thanks to all who supported this article with their expert advice and comments!

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!