The battle for Siegfried Line pillboxes in the Hürtgen Forest area (Published on 12/08/2022, supplemented on 12/11/2022)

A characteristic feature of the fighting in the Hürtgen Forest and its particular harshness is the Siegfried Line running through it and its structures – in particular pillboxes and shelters of various sizes –, sometimes hidden in dense forest and excellently camouflaged by the overgrowth over which fighting between the German and American troops was as fierce as it was full of victims in battles that, in part, surged back and forth for months.

After the war, it was often Julius Erasmus who recovered the German victims of the bunker fights in and around the Hürtgen Forest, identified them and buried them. Some of these battles will be described in more detail on this website as part of a series under the title “Pillbox Battles”, not least to remind us what war means to all involved.

For a better understanding and as a background for the following parts of the series, the situation will first be briefly described here in which the attackers and defenders of the Siegfried Line found themselves in the fall of 1944.

I. The Siegfried Line

The Siegfried Line, mostly called “Westwall” in German, was a military defense system along the western border of the German Reich that stretched for about 630 km from the Lower Rhine to the Swiss border. It was built in several stages between 1936 and 1940 and consisted of about 20,000 structures, in particular pillboxes and shelters of various sizes and functions, as well as tank traps, e.g. the so-called “Dragon’s Teeth”, ditches or walls. For more details on this very complex subject, please refer to the relevant literature (e.g. Bettinger/Büren, Der Westwall (1990) or Groß, Der Westwall zwischen Niederrhein und Schnee-Eifel (1982)).

II. The condition of the Siegfried Line in autumn 1944

In pre-war propaganda, German soldiers were told that the Siegfried Line was a “protective and insurmountable bulwark on the western border of the Reich”, but by the fall of 1944, when the war in the west reached the Reich’s territory, it was in many cases only a shadow of its former self. Participants of the battles have described in detail the situation they found at that time (on the condition of the Siegfried Line in the southern Eifel cf. Weidinger, Kameraden bis zum Ende, 4th ed. (1999), p. 321 ff. and Kramer, Der Krieg in der Schneifel September 1944 (1996), p. 538). After the German initial successes of the war, the equipment of the structures was often removed and moved further west to the Atlantic Wall. The rooms are damp, iron parts rusty, telephone connections – if still available – are not active. Ammunition, drinking water, rations and would dressing material are missing. Minefields, wire obstacles and often even doors have been removed; the fields of fire in front of the bunkers are overgrown. Many pillboxes have been misused in the meantime and are used e.g. as storage rooms. Their construction was also specifically designed for the weapons technology available at the start of the war; subsequent new and further developments such as the MG 42 or the Pak 7.5 (anti-tank gun 7.5), due to their deviating dimensions, no longer fitted into the appliances of the respective pillboxes and could therefore only be used in the open field.

The German troops moving into the Siegfried Line had been considerably decimated by the fighting in Normandy and often only had a fraction of their target strength left, so that in many sections only every third or fourth pillbox could be manned at all (cf. Kramer, ibid., p. 204). The German soldiers’ notions of the insurmountable Siegfried Line, nurtured unchanged by propaganda, met harsh reality in September 1944. Despite all the disappointment about the condition of the defense line, the concrete buildings nevertheless gave them a feeling of protection and security (cf. Kramer, ibid., p. 536).

III. The use of the pillboxes by the German forces

In addition to the structural and equipment deficiencies of the Siegfried Line structures, German troops were not sufficiently familiar with their tactical use when the fighting began in the fall of 1944. At least initially, they often understood the pillboxes as protected positions into which they would retreat in the event of an attack in order to conduct the battle from their supposedly safe interior. The idea, however, was to behave in a completely different way, but the German troops, many of whom were reserves with little or no military training, were not instructed accordingly (cf. Kramer, ibid., p. 536 f., translated from German language):

“Nobody tells these troops how to defend the Siegfried Line. No one tells them that the pillboxes, even the combat pillboxes, are first and foremost intended as shelters in case of artillery fire and bombing. When the tank and infantry attack begins, the crew must leave the pillbox as quickly as possible to fight the defensive battle from the field positions. Thus alone, all available weapons come to bear. Only the MG, which is permanently installed in the embrasure, fires from the pillbox. During the battle, the pillbox is the backbone of the defense. The wounded can be brought there, reserve ammunition is stored there, rations and water are stored there.”

The rather defensive behavior of the German soldiers in the early stages of the fighting favored the fighting of the pillboxes by the US troops and cost the lives of many German soldiers (cf. Kramer, ibid., p. 537). The German side quickly realizes that it is impossible to defend effectively from inside the pillboxes against the methods and means of attack used by the US side, and soldiers are ordered to set up field positions between the pillboxes and, in the event of massive attacks, to fight from there rather than from the pillboxes alone (cf. Weidinger, ibid., p. 326).

IV. The fight against the pillboxes by US troops

The US troops developed various tactics of fighting Siegfried Line pillboxes under a wide variety of conditions, often specifically aimed at first driving the German soldiers into the pillboxes in order to subsequently “smoke them out” and get them to surrender. If they refused to surrender, the pillbox was fought with most brutal methods (from the extensive US literature cf., for instance, the study “Breaching the Siegfried Line” by the XIX US Corps from October 1944).

For the purposes here, the following rough summary of some common procedures may suffice (from Rottman, World War II US Armored Infantry Tactics (2009), p. 50):

“The formidable ‘Siegfried Line’ or Westwall was breached in September and October of 1944. Units developed their own procedures for defeating bunkers. Typically, two or three tanks would approach a bunker from different directions after it and the surrounding area was barraged by artillery, assault guns, and mortars. This served to drive the defenders into the bunker from the two- and three-man fighting positions scattered around it (these potentially offered more resistance than the bunker itself). Most of the original antitank guns had been removed from the bunkers during the course of the war, leaving them defended only by machine guns. While tank main guns and MGs fired into embrasures and suspected fighting positions, the infantry assault teams moved in with bazookas, satchel charges, and sometimes flamethrowers. (…) Often the simple demonstration of firing a flame burst within the embrasure’s field of vision was all that was necessary to persuade the bunker’s defenders to wave a white flag. An even more successful tactic was the use of dozer tanks, (…) If the garrison refused to surrender, the dozer tank would first plow earth into the embrasures, and then bury the exits – the occupants usually trotted out with Hände hoch before that final step. Engineers would place 500 lb charges inside to collapse the bunker, preventing its reuse if recaptured during a counterattack.”

The US Army’s V Corps conducted its pillbox warfare as follows (cf. V Corps Operations in the ETO, 6 January 1942 – 9 May 1945, p. 258):

“A more or less flexible method of attack on the fortifications had been developed. When tank or tank destroyer support was available all units advanced as a team, the infantry moving into the assault with the tank. The apertures of the pillbox being assaulted and of the flanking pillboxes were covered with tank and small arms fire to keep them ‘buttoned up’. When the infantry reached a point 25 yards from the pillbox the tank fire ceased, and three or four of the nearest infantrymen covered the aperture with small arms fire while two flanking groups of three or four men proceeded to the rear of the pillbox. These men covered the rear entrance and apertures of the box. One man then walked down to the pillbox to attack it with grenades and bazooka fire. Usually the enemy would then surrender, but if not, the tank or self-propelled gun was brought around to blast in the rear of the pillbox. Once the position was taken, two or three men were left to destroy weapons in the pillbox, while the remainder of the group proceeded to take the next pillbox from the flanks and rear. Demolitions were brought up and the box destroyed.

Where no tank support was available, the method was similar except that a team of 16 to 18 men was used. This team worked up to the box, covered the apertures with small arms fire, while teams worked to the blind side of the box and with grenades, white phosphorus grenades, and TNT, blew the embrasure. Then, working from the top, a pole charge was placed against the door and the door blown. While this team operated, the support squad kept the supporting pillboxes closed up with small arms fire.

In either case, once the box was captured, measures were immediately taken to guard against counterattack by deploying to the front and flanks, and, if the position was to be maintained, digging in against the mortar and artillery fire which the enemy immediately laid down upon the positions.”

Manfred Groß explains (cf. Groß/Rohde/Rolf/Wegener, Der Westwall – Vom Denkmalwert des Unerfreulichen (1997), p. 105, translation from German language):

“Although the pillboxes offered protection from artillery fire and bombs – with a ceiling thickness of 2 meters up to a 500 kg bomb – they became deadly traps for the German defenders deployed there once the enemy succeeded in driving the crew, who were dug into positions outside, into the pillboxes by artillery fire. If the men did not comply with the order to surrender, the attacker tried to force them to surrender by firing at the doors and embrasures. If that did not help either, tanks equipped with scraper shields pushed earth in front of the entrances and embrasures, or the infantry used explosives to try to destroy the bunker along with its occupants. American field reports captured by the Germans on the methods used to capture bunkers were translated and made known to the pillbox crews so that they could take appropriate measures to protect themselves against such attacks.”

In view of this, it becomes clear that the Siegfried Line pillboxes were by no means “impregnable bulwarks” for their crews, at least under the conditions prevailing in the fall of 1944, as German propaganda continued to claim, but often traps whose only way out led to imprisonment or death. However, where getting the the heavy weapons used by the US forces against the pillboxes in place encountered major obstacles, where the pillboxes could not be sustainably engaged by direct artillery fire, where the terrain favored the defenders and they could be supported by their own artillery fire, the crews sometimes held their pillboxes against the American attacks for months, e.g. in the Raffelsbrand section in Hürtgen Forest (cf. Groß/Rohde/Rolf/Wegener, ibid., p. 104).

V. The German defenders: Surrender or die in the pillbox?

The above descriptions already show that the US troops were able to draw on their full resources in their action against the structures of the Siegfried Line. The defending German crews, in many cases already consisting of very young or old, often inadequately trained and equipped men, had nothing to oppose and mostly surrendered in the face of the heavy shelling and the obvious material superiority of the US soldiers.

However, cases have also been described in which pillbox crews refused to surrender for hours, even in the face of the most intense US attacks, and persevered in their pillboxes, sometimes to their deaths. Manfred Groß explains (cf. Groß/Rohde/Rolf/Wegener, ibid, p. 106, translation from German language):

“The battle for the individual pillboxes claimed many casualties, especially among the defenders who, once they were trapped in the bunkers and had closed the embrasures in the face of the enemy’s preparatory fire, were unable to defend themselves to the outside. In many cases, the surrender of the pillboxes demanded by the enemy was refused by the trapped crews, so the enemy was forced to destroy the installation together with its crew.”

This behavior is often attributed to the pillbox crew’s fear of court martial in light of the command situation at the time, e.g. to the so-called “Haltebefehl” (“Holding Order”) issued on 14/09/1944 by the then German Commander-in-Chief West, General von Rundstedt, which read as follows (cf. Groß/Rohde/Rolf/Wegener, ibid., p. 106, translated from German language):

“1) In the battle for Germany, the Siegfried Line is of decisive importance!

2) I order: The Siegfried Line with each of its individual installations is to be held to the last bullet and until complete destruction. This order is to be announced immediately to all command authorities, units, combat commanders and troops.”

However, this does not go far enough. For the individual soldier, the following announcement by the Reichsführer SS, Heinrich Himmler, of 10/09/1944 might have been much more important than the fear of court martial (quoted according to Shulman, Defeat in the West (1947), p. 218):

“Certain unreliable elements seem to believe that the war will be over for them as soon as they surrender to the enemy. Against this belief it must be pointed out that every deserter will be prosecuted and will find his just punishment. Furthermore, his ignominious behavior will entail the most severe consequences for his family. Upon examination of the circumstances, they will be summarily shot.”

The Wehrmacht subsequently also acted in the spirit of this announcement, as is shown by an appeal read out in November 1944 to all members of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division, which was fighting against US troops in the Eifel. After calling out six alleged deserters by their full names, it reads (quoted according to Shulman, ibid., p. 219):

“These bastards have given away important military secrets. The result is that for the past few days the Americans have been laying accurate artillery fire on your positions, your pillboxes, your company and platoon headquarters, your field kitchens and your messenger routes. (…) As for the contemptible traitors who have forgotten their honour, rest assured the division will see that they never see home and loved ones again. Their families will have to atone for their treason. (…)”

In an order issued by the commander of the 1st Army, General von Obstfelder, in early December 1944 which can be retrieved from the Federal Archives, under the title “Weisung für die Kampfführung im Westwall” (“Directive for combat conduct in the Siegfried Line”), it is stated, among other things (cf. document BArch RH 30/18, translated from German language):

“1.) The Siegfried Line is a line that must be held at all costs, only dying is possible there.

(…)

10.) Cowardice and softness are to be countered with the harshest means. Anyone who abandons his fighting position when attacked by the enemy is to be shot immediately without trial.

11.) Leaders of all grades are to be briefed immediately on the combat directive. Implementation is to be reported to the Army by 8/12/44.

12.) When taking over new sections of the Siegfried Line, the commanders of the buildings and fighting positions are to be obliged in writing to hold their fighting positions until the last. Implementation is to be reported to the army after occupation of the fighting stands.

13.) The obligation of current security crews is to be carried out in the same manner, implementation to be reported to the Army by 10/12/44.”

These were the general conditions for the German defenders during a US attack on the pillbox they occupied. By virtue of the order, they had to persevere to the last, if necessary to death. If they did not comply and gave up, or even tried to do so, they were threatened with death for this reason alone. Even if the corresponding order was not implemented, they could give up, go into captivity and spare their lives and health for the time being, but, in doing so, putting at risk the well-being and fate of their relatives at home in view of the retaliatory measures expressly threatened for this behavior. Or they protected their lives and those of their families from retaliation from their own ranks and remained in their bunker even in the face of the most brute measures of the US troops. Thus, the perseverance of many a German soldier in his Siegfried Line pillbox even in the face of massive US attacks may be explained less by obeying orders or a belief in the “Endsieg”, which was in any case widely lacking in the fall of 1944, than by the massive threats and sheer concern for the consequences for his family if he surrendered. One can imagine the cruel conflict of conscience that these soldiers were exposed to and that might have moved many of them to prefer to go to their deaths in order to protect their relatives.

For some of these fights for Siegfried Line pillboxes in the Hürtgen Forest area, whose dead were later often recovered by Julius Erasmus, there are eyewitness reports from the German or American side, which describe the events in detail. Some of these reports will be reproduced here in the series “Pillbox Battles”.

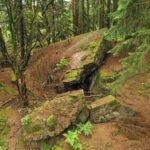

(Head picture: Pillbox 139/40 in the Buhlert area close to Strauch, March 2022)

If you wish to support my work, you can do so here. Many thanks!